Talk of a Third Intifada: Where to from Here, Palestine?

By Ramzy Baroud

When a journalist tries to do a historian’s job, the outcome can be quite interesting. Using history as a side note in a brief news report or political analysis oftentimes does more harm than good. Now imagine if that journalist was not dependable to begin with, even more than it being “interesting”, the outcome runs the risk of becoming a mockery.

Consider the selective historical views offered by New York Times writer Thomas Freidman - exposed in the book “The Imperial Messenger” by Belen Fernandez for his pseudo- intellectual shenanigans, contradictions and constant marketing of the status quo.

In an article entitled, The Third Intifada, published last February, Friedman attempts to explain two of the most consequential events in the collective history of the Palestinian people, if not the whole region: “For a while now I’ve wondered why there’s been no Third Intifada. That is, no third Palestinian uprising in the West Bank, the first of which helped to spur the Oslo peace process and the second of which - with more live ammunition from the Israeli side and suicide bombings from the Palestinian side - led to the breakdown of Oslo.”

Ta-da, there it is: Palestinian history for dummies, by, you know .. Friedman. Never mind that the consequences that led to the first uprising in 1987 included the fact that Palestinians were rebelling against the very detached elitist culture, operating from Tunisia, which purported to speak on behalf of the Palestinian people. It was a small clique within the PLO-Fatah leadership that were not even living in Palestine at the time who signed a ruinous, secret agreement in Olso in 1993. And, at the expense of their people’s rightful demands for freedom, this arrangement won them just a few perks. The uprising didn’t help “spur the Oslo peace process”; the ‘process’ was rather introduced, with the support and financing of the United States and others, to crush the intifada, as it did.

While there is some truth to the fact that the second uprising led to the breakdown of Oslo, Friedman’s logic indicates a level of inconsistency on the part of the Palestinian people and their revolts - that they rebelled to bring peace, and they rebelled again to destroy it. Of course, his seemingly harmless interjection there of Israel’s use of live ammunition during the second uprising (as if thousands of Palestinians were not killed and wounded by live ammunition in the first), while Palestinians used suicide bombings - for the uninformed reader, justifies Israel’s choice of weapons.

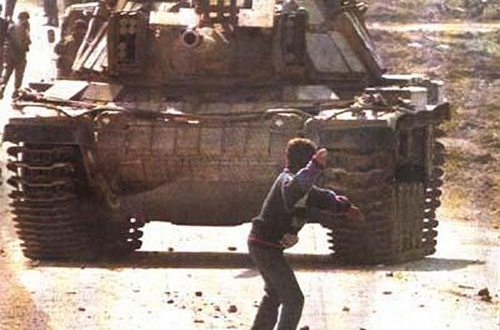

According to the Israeli rights organization B'Tselem, 1,489 Palestinians were killed during the first intifada (1987-1993) including 304 children. I85 Israelis were reportedly killed including 91 soldiers.

Over 4,000 Palestinians were killed during the second intifada, and over a 1,000 Israelis. However, according to B’Tselem, the high price of death and injury hardly ceased when the second Intifada was arguably over by the end of 2005. In “10 years to the second Intifada,” the Israeli organization reported that: “Israeli security forces killed 6,371 Palestinians, of whom 1,317 were minors. At least 2,996 of the fatalities did not participate in the hostilities when killed. .. An additional 248 were Palestinian police killed in Gaza during operation Cast Lead, and 240 were targets of assassinations.”

There are other possible breakdowns of these numbers, which would be essential to understanding the nature of popular Palestinian revolts. The victims come from diverse backgrounds: refugee camps, villages, small towns and cities. Until Israel’s devastating war on Gaza, 2008-09, the numbers were almost equally divided between Gaza and the West Bank. Some of the victims were Palestinians with Israeli citizenship. Israeli bullets and shells targeted a whole range of people, starting with bystanders, to un-armed protesters, stone throwers, armed fighters, community activists, political leaders, militant leaders, men, women, children, and so on.

In some tragic way, the Israeli responses to Palestinian uprisings is the best validation of the popular nature of the intifada, which goes against every claim made by Israeli leaders that say intifadas are staged and manipulated for specific political ends.

For years, many journalists have busied themselves asking or trying to answer questions regarding the anticipated Third Intifada. Some did so in earnest, others misleadingly, as in the NBC News report: Palestinian Violence Targets Israelis: Has Third Intifada Begun? Few took a stab at objectivity with mixed results as in CNN's: In Jerusalem, the 'auto intifada' is far from an uprising.

But most of them, using a supercilious approach to understanding the Palestinian collective, failed to understand what an uprising is in the first place.

Even the somewhat sensible approach that explains an intifada as popular outrage resulting from the lack of political horizon can, although at times unwittingly, seem distorted.

It is interesting that hardly any had the astuteness to predict previous uprisings. True, violence can be foreseen to some degree, but the collective course of action of a whole nation that is separated by impossible geographical, political, factional and other divides, is not so easy to analyze in merely a few sentences, let alone predict.

There were numerous incidents in the past that never culminated into an “intifada”, although they seem to unite various sectors of Palestinian society, and where a degree of violence was also a prominent feature. They failed because intifadas are not a call for violence agreed upon by a number of people that would constitute a critical mass. Intifadas, although often articulated with a clear set of demands, are not driven by a clear political agenda either.

Palestinians lead an uprising in 1936 against the British Mandate government in Palestine, when the latter did its most to empower Zionists to establish a ‘Jewish state’, and deny Palestinians any political aspiration for independence, thus negating the very spirit of the UN mandate. The uprising turned into a revolt, the outcome of which was the rise of political consciousness among all segments of Palestinian society. A Palestinian identity, which existed for generations, was crystallized in a meaningful and much greater cohesion than ever before.

If examined through a rigid political equation, the 1936-39 Intifada failed, but its success was the unification of an identity that was fragmented purposely or by circumstance. Later intifadas achieved similar results. The 1987 Intifada reclaimed the Palestinian struggle by a young, vibrant generation that was based in Palestine itself, unifying more than the identity of the people, but their narrative as well. The 2000 Intifada challenged the ahistorical anomaly of Oslo, which seemed like a major divergence from the course of resistance championed by every Palestinian generation since 1936.

Although Intifadas affect the course of politics, they are hardly meant as political statements per se. They are unconcerned with the belittling depictions of most journalists and politicians. They are a comprehensive, remarkable and uncompromising process that, regardless of their impact on political discourses, are meant to “shake off”, and defiantly challenge all the factors that contribute to the oppression of a nation. This is not about “violence targeting Israelis”, or its collaborators among Palestinians. It is the awakening of a whole society, joined by a painstaking attempt at redrawing all priorities as a step forward on the path of liberation, in both the cerebral and actual sense.

And considering the numerous variables at play, only the Palestinian people can tell us when they are ready for an intifada - because, essentially it belongs to them, and them alone.

The Arab Democrat The Latest From The Arab World

The Arab Democrat The Latest From The Arab World